“The

fool on the hill sees the sun going down, and the eyes in his head,

see the world spinning 'round.” – Paul McCartney

Last

year, 43 people met their fates at the hands of government

employees who were commissioned to snuff out the life of America's

most notorious criminals. People, of course, like to argue about the

merits of capital punishment and whether or not the government should

be in the business of offing its most loathsome citizenry, but I'll

save all my arguments for it and against it until another day. Today,

I want to talk about “Fools,” and I have a good story about

someone who was once executed on death row that illustrates the

rhetorical point I want to make.

The

number of people killed by the government, with full intent and in

front of reporters who witness the event in order to write about it,

is down by more than half since 1999 when we ended the Millennium off

with a bang by launching 99 criminal explorers into the dark void of

The Great Unknown. One of the first lessons they teach in a basic

news reporting class is the list of values that make a story

“newsworthy” typically includes such factors as

prominence, proximity, timeliness, impact, and human interest. Even

when we're knocking off the nation's ne'er-do-wells on almost a

weekly basis, it makes for a pretty good news story; however, back in

1966, when the country went that entire year with only being able to

check off one name from its list of people on Death Row, putting

someone into an electric chair to toast the soul out of them made an

exceptionally good news story.

James French was only thirty years old

when the State of Oklahoma strapped him into an electric chair and

sent his wind sweeping down the plain, but by then, he was ready for

it. French was one of those people your parents warn you about when

you are learning to drive and you're tempted to pick up hitchhikers.

Contrary to traditional parental wisdom, not everyone who is

meandering around this country by sticking out a thumb and taking

rides from strangers will kill you – I, for one, hitchhiked from

Athens, Ohio to Yellowstone National Park and back when I was a

vacuous college student, and I made the whole trip without killing

anyone. French, however, was one of those horror movie type of

hitchhikers who pretty much ruined it for all the nonviolent ramblers

who are simply out to score a free ride. I don't know if it was just

a rookie mistake or what, but French had only made it from Texas to

Oklahoma when he decided to take his benefactor hostage for a while

and then kill the fellow for his car.

After French was caught and he came to

the inescapable conclusion that he was going to have to live out the

rest of his days in prison, French decided he would rather have the

management shorten the length of his stay rather than prolong it.

Three years into his new career as a lifer, French murdered a

cellmate in order to insure that he could get his name added to the

list of people waiting for a coveted oneway ticket to ride Old Sparky

to the Outer Banks of Eternity. Back in the mid 60's, it was easier

to catch a ride in a rusty pickup truck on a dusty two-lane road in

Texas than it was to secure a seat in an Oklahoman electric chair.

Perhaps it was the heat of that hot

day in August of 1966 when French took his final walk that inspired

him or maybe he'd been thinking about it from the moment he found out

he'd won his chance to be the only guy to be killed by the government

that year, but French came up with the perfect rejoinder to the

reporters who were anxious to have a good quote from the prisoner

when they asked him, “Do you have any last words?” French said

to them, “Hey, fellas! How about this for a headline for tomorrow’s

paper? ‘French Fries’!”

This type of sardonic remark is what

separates genuine fools from mere posers. Contrary to whatever you

have heard, fools are not stupid. Fools recognize where they are and

who they are with, and nonetheless, they say whatever's on their mind

without regard for its propriety or its ramifications for themselves

or others. A genuine fool isn't courageous in face of danger; a fool

is unconcerned by it.

There are lots of ways of dividing

people into two groups: the rich and the poor, the young and the old,

and those who prefer chocolate over vanilla – to name a few.

Separating people into the groups “the intelligent and the obtuse”

doesn't really get at identifying the qualities of fools because

fools are neither intelligent nor obtuse. Fools exist in a space

that is not defined by their degree of knowledge or intelligence, but

is distinguished, rather, by their heedless behavior. There are

people who support the systems that direct their lives (call them

“followers,” perhaps); there are people who fight against the

systems that direct their lives (call them “rebels”); and there

are the people for whom the system doesn't really come into their

decision making – not because they rage against it or want to

challenge its prescriptions, but because they simply don't believe

the rules that applies to everyone else actually applies to them, and

these are the people who merit the title “fools.”

A rebel can be an idealist who images

a better world in which the systemic order that controls people's

lives has changed, and a rebel can be willing to accept the

consequences of challenging the system that controls them. A rebel

understands (or at least works under the assumption that he or she

understands) the motives of the authoritarian forces that are in

control, and the rebel operates to subvert the powers that are

indifferent to their notions of injustice. A fool, on the other

hand, is no rebel. A fool has no desire to change the system because

the fool is either unaware of the system or believes the system is

unaware of them. A fool isn't necessarily stupid and willing to

sacrifice his or her own dignity to appease the Powers That Be; a

fool lives unconcerned with the opinions of the Powers That Be

because the fool is too preoccupied with living in a world defined by

the fool's own epistemological boundaries.

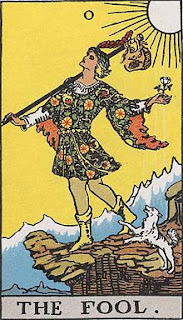

In many card games, the Joker is a

wildcard that can replace any other card and thus, act like a magical

card that randomly appears from a player in need of taking a hand.

In the original games based upon the Tarot decks where “The Fool”

(the card that later became the Joker in modern decks) appears, “The

Fool” card does not replace another card (that is to say it

takes on the identity of another card) it merely temporarily excuses

the player from following suit. Thus, the original wildcards were

not like cards with superpowers that could suddenly out-trump any

other card on the table, the purpose of the original Jokers were to

create a space for the player where the rules were temporarily

suspended and did not apply to the player. Thus, fools are neither

people who either seek to win by following the order supplied by the

rules nor are they people who seek to change the rules for the

benefit of themselves and others; fools are people who simply exist

outside of the game, and they allow us to recognize how we are

playing the system that they, themselves, cannot recognize. That's

enough for now to think about. As we approach the first day of

April, let's just remember that people do not choose to be fools,

fools are merely who they are.

Keep thinking rhetorically and I'll be

back in a couple of weeks. I'll be taking next weekend off to spend

time with the family and to recover from an anticipated

overconsumption of chocolate bunny ears.